This is a chapter from the book Mixed, published by The Nasiona. Nicole Zelniker’s Mixed, a work of journalism about mixed-race families and their shifting identities, is available now in paperback and on Amazon Kindle.

From the American Psychological Association: Multiracial children are now the largest demographic under the age of 18 in the US.

“Race. Wow.” Lynda Gomi, a white American woman, turned to her husband, Kazuhiro, who is Japanese and from Japan, and continued. “So, I guess, from our experience, I would say culture is the bigger difference. And that could be socioeconomic culture, or that could be Japanese culture, American culture.”

Lynda and Kazuhiro Gomi sat at their dining room table in Laura Generale’s hometown of Dobbs Ferry, New York. Lynda and Kazuhiro met while Lynda was teaching in Japan, several years ago. Every year, more than 450,000 US citizens marry non-US citizens, according to the US Department of Commerce, or about 0.14 percent of the population. The Ministry of Health cites that in Japan, the number of Japanese citizens to marry non-Japanese citizens was about 21,488 in 2013, or about 0.02 percent.

“I think your culture has nothing to do with your DNA,” Kazuhiro added. “It’s just the environment creating human characters. When I hear race, I think it’s more scientific. For example, I think there are some specific diseases that certain races are more susceptible to. So those things, to me, are race.”

The couple has moved back and forth several times since marrying, though they have been in the US, in Dobbs Ferry, for more than a decade. While about 81 percent of the population in Dobbs Ferry is white, the next biggest population, Asian, is just under 8 percent. Japan, on the other hand, is racially homogeneous, nearly 99 percent Japanese. Smaller populations include Koreans, Chinese, and Filipinos, according to an article in Asia Times.

“Well, I think both cultures have small-minded people,” said Lynda. “But Japanese culture in particular focuses on who’s in the group and who’s outside of the group, so pointing at people and identifying them as outside of the group is kind of the norm. Children would always point at me and say ‘foreigner’ or ‘outside person.’”

“Living in America, you have to act like an American,” said Kazuhiro. “That’s important.” At the same time, Kazuhiro said, “The US culture is obviously more of a melting pot, especially in New York. I think it’s important to have your identity. Everybody, I think, living here, has their own identity.”

In terms of the culture, “I think that the US has more culture allowing, and also people are really proud of that ethnic heritage,” he said. “That’s definitely very different.”

He added, “In Japan, if some American or some other people came to live in Tokyo and tried to stand out, saying ‘I’m an American,’ probably the people around them would take it differently and probably more negatively. I’m learning that that’s quite different here.”

“But remember what happened in Michigan?” Lynda asked. “We were visiting my parents up in this small little town in Michigan. I kept saying, ‘We’re going to get to America and you’re just going to feel so welcome. You’re just going to look like everybody else.’ I had grown up in a much bigger city and had moved to this smaller town.”

She continued, “The first time we go out of the house, we’re in this grocery store, a man comes up to him and says, ‘Are you Japanese? I fought in World War II.’ It wasn’t in a negative way. He just wanted to share his experience. I guess he was there after the war and he met people there and he wasn’t being negative. But I was like, ‘Wait a minute, how come you’re being pushed into the outside category? This isn’t supposed to be happening.’”

Both in the US and in Japan, Lynda is a teacher. She said she always tries to push the boundaries of what it means to be Japanese in Japan or American in the US.

“When I was teaching junior high, high school, we would have this discussion about what it means to be Japanese,” she said. “And I would say, ‘Well how long have you lived here?’ They would say, ‘15 years,’ and I would say ‘I’ve lived here longer, so I guess I’m more Japanese than you are.’ And they would say, ‘Oh, no, no, no, no, you can’t be more Japanese.’ So, I kind of like to push those boundaries, to get people to think beyond the ‘You don’t look like me, so you’re outside.’”

When Lynda went to work in Japan as a teacher, she was only given one instruction from her parents: come home single. Though she failed to do so, her parents forgave her as soon as they met Kazuhiro.

“They immediately fell in love. They liked him better than me right away,” she joked.

Kazuhiro’s parents were very accepting of Lynda, as well. Although it was hard for both sets of parents to know that their children would be spending a lot of time in another country, Kazuhiro’s parents did have experience interacting with people outside of Japan.

“My father was in international companies, so he was very exposed to other cultures,” Kazuhiro said.

“He traveled,” said Lynda. “And your mom went with him.”

Kazuhiro nodded. “Yeah, my mom went with him for business trips and stuff. So they were pretty exposed. They actually liked to have American college students do the homestay.”

“That’s how we met,” said Lynda. “My college roommate’s brother stayed at his house.”

“My mom once told me, I don’t know if she remembers, ‘You can have a non-Japanese wife, I don’t care. Do whatever you like,’” Kazuhiro added.

Soon after they married, Lynda and Kazuhiro had their first child, a boy they named Kiyota. Several years later, they had a daughter, a girl named Aila. Both children spent most of their early years back and forth, spending the year in Yokohama, Japan, and summers in the US.

“Kazu’s job at that time was with a domestic telephone company and, so we would be living in Japan,” said Lynda. “We decided that we would speak English in the home, and when we were outside, we would speak Japanese. His parents lived very close, so when they were around, we would speak Japanese around them. We would get the kids to the US every summer, so a huge part of our budget was dedicated to that airplane fare. And my parents had space that we could stay in while we were here.”

Though Kazuhiro’s job had been in Japan, Lynda knew she wanted her children to come to the US for college.

“Japanese gets you this great foundation of facts and knowledge, but then college doesn’t help you use it,” she said. “So, that whole critical, analytical thinking piece that’s so important a focus in Western schools, I wanted my kids to have that.”

Both Lynda and Kazuhiro agree that it was easy for them to flip back and forth between languages, at least compared to other couples they have known.

“I belonged to a group of women married to Japanese men,” said Lynda. “There were a lot of different situations, so in many cases, the husbands hated English and let that attitude be known. So, we certainly didn’t have that. We both shared positive perspectives with the kids.”

“In that regard, I think we both wanted the kids to be bilingual, bicultural,” said Kazuhiro.

Lynda added, “We both respected each other’s culture and we wanted our children to have both.”

Though their children are now adults, Lynda remembered a time when Kiyota had to cope with bullying from other students.

“I remember Kiyo coming home from first grade and a boy was teasing him,” she said. “The boy was calling him ‘French underwear,’ which sounds a little bit like ‘French bread’ in Japanese. And I just burst out laughing. It was so stupid because, well, we’re not French, first of all. And I think I’ve always been so happy that my response was to laugh rather than getting crazy and blowing up because than it would have made him tense. And this kid actually ended up being his best friend by sixth grade. The two of them were inseparable.”

Kazuhiro and Lynda also said that while the children were very conscious of being mixed from a young age, it’s hard to actively be both Asian and white.

“Whenever they would be walking with me, I would be getting pointed at which means they would be getting pointed at,” said Lynda about Japan.

“I would say, yeah, they were pretty conscious about it,” Kazuhiro added.

“One of my regrets is that they haven’t gotten to the point where they really are both,” said Lynda. “Growing up in Japan, they were Japanese. When they were here, they had English-speaking friends. They didn’t have Japanese friends. So, they were either one or the other. And that blending didn’t really happen.”

***

Looking to the future, both Lynda and Kazuhiro cannot help but think about the Trump administration, although Kazuhiro is more optimistic than Lynda.

“One person I don’t think can turn this whole ship to the wreck,” said Kazuhiro. “There’s definitely a whole system. The US has managed to maintain the checks and balances.”

“Well, we thought we did,” Lynda said. “We’re discovering that we didn’t.”

“I’m not so paranoid about my own individual situation,” said Kazuhiro. “I’m more worried about the whole world. I think I’m most worried about the reputation about the United States of America from the rest of the world. I think people used to have all the respect and admiration for the US. I think that is going away every day.”

“Every tweet,” Lynda joked.

“I think that’s really hard to regain if you lose it,” said Kazuhiro. “It takes more than four years to do so.” Of the Japanese government, Kazuhiro commented, “I think the Japanese government has no choice but following the US government right now because of the North Korea situation. We need someone to protect the country, so the Japanese government has no choice. I think the Japanese people in general, no one supports Trump.”

Lynda and Kazuhiro are both involved in the Japanese American Association of New York. More recently, the organization has become focused on what is happening with Muslims in the US, largely because of Trump’s proposed Muslim ban. Though his ban did not take place, Trump has also suggested a Muslim registry, which would mean the estimated 3.3 million Muslims living in the US would have to become a part of a public registry according to Pew. This has been compared to Hitler’s keeping track of the Jewish residents in Nazi Germany during World War II.

Many also fear that a Muslim registry would lead to mass internment, such as with the Japanese Americans in the US during the same time period. This has opened the floodgates for the organization, and the Japanese-American community as a whole, to become politically active.

“Their relatives were interned during World War II, so they are identifying with the Islamic community and reaching out to the Islamic community,” said Lynda. “After the war, the families were ashamed that they had been put into a concentration camp and all of their possessions taken away from them. You put it behind you by being quiet. They didn’t have conversations with their children, but now their grandchildren and great grandchildren are saying, ‘Come on, tell us, tell us.’”

She continued, “So now, in this environment, they’re going back to their relatives and the relatives are like, ‘You want to hear my story? But my story’s not important.’ It’s really important because this is going to happen again. They start telling this story to the family that they’ve never told before. So, very exciting.”

Even further into the future, Lynda and Kazuhiro are looking forward to seeing what Kiyota and Aila do with their lives. Kiyota lives in Boston, Massachusetts, which is 46 percent non-Hispanic white and 9 percent Asian as of 2015. Aila lives in Cleveland, Ohio, 33 percent white and less than 2 percent Asian. The largest population in Cleveland is black—53 percent based on the 2010 census.

Both Kiyota and Aila ended up going to school in the US, just as Lynda had planned. Kiyota went to Carlton College for his undergraduate degree, which is 62 percent white and nearly 9 percent Asian, and Boston University for graduate school, which is 40 percent white and 14 percent Asian among the undergraduate students. Aila went to Case Western Reserve University, which is 50 percent white and 20 percent Asian.

Both Kiyota and Aila’s choices to stay in the US for college may have been influenced by the fact that, once the family moved to the US for good, they spoke almost entirely English. Lynda said she gave up speaking Japanese in the house after she realized she was speaking it more than Kazuhiro or the kids.

“We used to be really good about it when his parents were around, and we would speak in Japanese around them,” she said. “Maybe not so much anymore. Language is a habit, and once you get comfortable with your habit, changing really takes some serious determination. Kiyo did take Japanese in college, but in his career has not used Japanese or sought that as a way to give him a step up and be ahead of everybody else.”

“I’m hoping that the both of them maintain some culture from Japan and implement it into their family traditions,” said Kazuhiro. “I believe they will. That’s what I’m hoping for.”

“Definitely the food side,” Lynda said. “But interestingly, I think Japanese New Year is more important than Christmas to them. Christmas was just our small little family group. It wasn’t a whole big craziness. But New Year’s was going to visit their great uncle and great aunt and distant cousins. So that—well, again, the whole culture was celebrating Japanese New Year. Kiyo is making a point to come home for New Year’s.”

About the Author

NICOLE ZELNIKER is a graduate of the Columbia Journalism School and an editorial researcher with The Conversation US. Her work has appeared on The Pulitzer Prizes website and in USAToday and Yes! Weekly, among other places. A creative writer as well as a journalist, Nicole has had several pieces of poetry published including “Cracks in the Sidewalk” (Quail Bell Magazine) and “Surge” (The Greenleaf Review), as well as three short stories, “Last Dance” (The Hungry Chimera), “Dress Rehearsal” (littledeathlit), and “Lucky” (Fixional). Mixed is Zelniker’s first book.

NICOLE ZELNIKER is a graduate of the Columbia Journalism School and an editorial researcher with The Conversation US. Her work has appeared on The Pulitzer Prizes website and in USAToday and Yes! Weekly, among other places. A creative writer as well as a journalist, Nicole has had several pieces of poetry published including “Cracks in the Sidewalk” (Quail Bell Magazine) and “Surge” (The Greenleaf Review), as well as three short stories, “Last Dance” (The Hungry Chimera), “Dress Rehearsal” (littledeathlit), and “Lucky” (Fixional). Mixed is Zelniker’s first book.

Follower her on Twitter and Instagram.

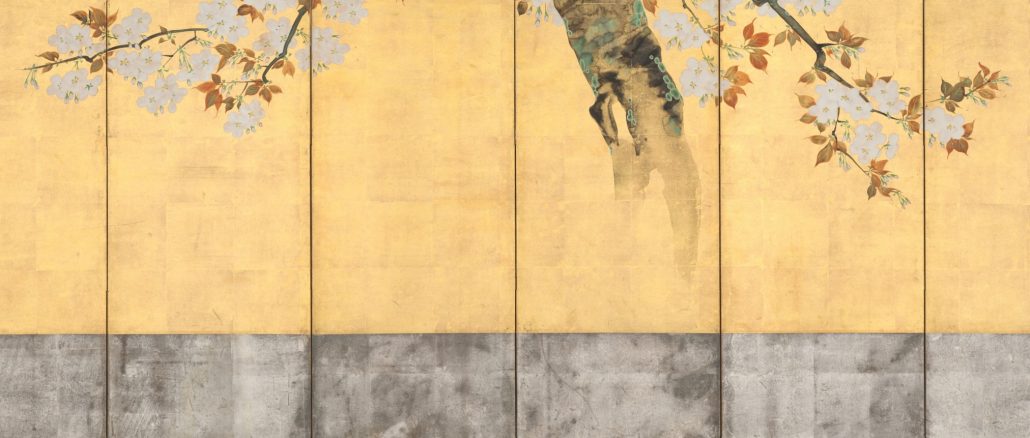

Featured image: Sakai Hōitsu, “Blossoming Cherry Trees,” pair of six-panel folding screens; ink, color, and gold leaf on paper; ca. 1805. Mary Griggs Burke Collection. Gift of the Mary Jackson Burke Foundation, 2015. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Check out Zelniker’s other chapter, “Jujubes Represent Sugar,” in The Nasiona here.