Being an immigrant can be exhausting. They tell you to assimilate, when they’re really asking you to give up your roots. They tell you to learn the language, when they’re really asking you to forget your mother’s tongue. They tell you to become an American, when they’ll never fully recognize you as one of them.

Maybe that’s the whole point: Forget where you came from, now you’re here. (For the few allowed to stay.) Build a new life. Start afresh, no matter what you left behind.

A pointless plea. Because our bodies, they can’t forget.

I’ve been told it’s hard to find home when you’re an immigrant, and I think that’s exacerbated when you come from a long line of migrants; when a migration journey was made in nearly every generation of your family for the past one hundred and fifty years.

All four of my maternal grandmother’s grandparents left Ireland for Argentina in the late 1800s. They were searching for land to work on.

My maternal grandfather left Italy for Argentina as a child in the 1920s. His family was fleeing fascism.

My paternal grandfather left Spain for Argentina as an adult in the 1950s. He, too, was fleeing fascism.

My parents, two brothers and I left Argentina for the U.S. in the 1990s. We were seeking better economic opportunities.

I left the U.S. for Spain in 2017. I was seeking answers: a career, a more fitting culture, a home.

I’ve been searching for home my entire life, and I’m not sure I’ll ever find it.

*

I never thought I’d miss Austin, Texas, when I moved to Barcelona, Spain.

Personally, the Mediterranean city is a much better fit: there’s the beach, the mountains, food from all over the world, people speaking dozens of languages, narrow pedestrian streets with antique book stores that smell of my grandmother’s house. There are countless outdoor cafés with cheap, delicious coffee.

It doesn’t have my friends, but I’ve made new ones, and I chat with my old ones through WhatsApp. It doesn’t have my family, or my dog. That I can’t replace.

Since the coronavirus pandemic began, though, I’ve wanted nothing but to go back to Austin. Not just to see my friends and family, but to be there. I want to see the wide suburban streets where I once rode bikes, eat at all the diners we snuck into in high school when we skipped class. I want to read through my stack of old diaries, dating back to when I was five years old, and whose language, over the years, changed from Spanish to English (sometimes Spanglish). I want to hear the screaming grackles, bird noises I cannot quite recall unless I look up videos on YouTube. I want to smell bar-be-cue. I want to smell Mexican food. I want to eat pecan pie.

I want the familiar. I want to hug my mom and dad; I want to smell them. I think I’ve forgotten what they smell like, but no, I don’t want to think about that. I want to eat my mom’s empanadas. Not the “Argentine empanadas” the Catalans sell here for two Euros fifty. I want my mom’s. And my dad’s arroz con leche.

I can’t stop watching shows set in U.S. suburbia because they remind me of my childhood. I want it to be September 1999: my first weeks of fifth grade, with my crisp-white notebooks and freshly sharpened pencils. They smell like what I imagine forests smell like. I’m one of the weird kids who likes to learn, and I take several nights to practice my presentation on snow leopards. I still have to work on my English accent, but I’m confident enough to write the research paper without my mom’s help.

When I think of what home feels like, now, I think of those days. But did I think of Austin as home then? Did I think of the concept of home at all?

I want to bury my face in my dog’s furry mane, but that I know I can’t do anymore. My dog died in Austin six months into the pandemic. Now the house I’ve known for the past 16 years is not the same house. It cannot be the same house without his clumps of hair rolling around like indoor tumbleweeds.

*

The most difficult thing about being far from home — or, in my case, from multiple homes — are the deaths. And it’s never been more exacerbated than right now, during a deadly pandemic. I keep hearing of people’s relatives dying. Some of our own family friends have died.

People love to tell me that “it can happen even when you live in the same city,” but people who say this have never lived far from home. I don’t care if deaths can also catch me off-guard when we live in the same place; I care that I haven’t seen the person who just died in several years. I care that every time I say goodbye, it could be the last goodbye. I care that I missed so many opportunities to get together for dinner or coffee or a stroll to hug these loved ones.

I’m terrified of what could happen in the time in between visits. I’ve already lost an aunt, a grandfather and an uncle this way.

And I’m one of the lucky ones. In pre-pandemic times, I could travel to all these places. None of my family or friends live in countries ravaged by war or violence, so the threat of death is less eminent. At least it was, until this year.

For the past four years, on my yearly visit to Texas, I would cry uncontrollably when I said goodbye to my dog. He was getting older; I knew the chances of that something happening were higher. He usually looked at me in shock and tried to walk away — he didn’t like it when people cried or were angry, it scared him for some reason. It’s like he confused the two emotions: anger and sadness. He saw them as one possible threat. Maybe he was right: we can act violently when we’re angry or when we’re sad. Oftentimes the two emotions come together.

*

During the 18 years I lived in the States, I felt homesick for Argentina many times.

At first, that homesickness was blurry, or maybe just confusing. On the one hand, as a nine-year-old girl, I was ecstatic about the novelty of our life in the U.S.: the big house, the expansive backyard, the puppy that came home with us one afternoon, asleep in the backseat of our new (to us) car that smelled of recently washed carpet.

On the other hand, I wanted to see my aunts, my older cousins who felt more like protective siblings, my newest cousin who was barely a year old. I don’t particularly remember asking for them; I think I understood they were far away, only reachable by phone or letters. I would write them in various colored gel pens, pasting sparkly stickers on the corners of rule-lined paper. Sometimes we would set up a date to place long-distance phone calls with our family and friends.

“One day we’ll be able to chat through a computer and see each other through video in real time,” I once heard my uncle say over the receiver. It seemed like an incomprehensible future.

But the homesickness that I distinctly remember — the kind that pierces your body with the heavy realization that you can never go back to that exact place because too many years have passed by — came as I got older. These bouts of nostalgia mostly surfaced during birthdays or holidays, when the promised video calls were finally a thing, surprising me with their fast arrival. I’d watch family members in their summertime Christmas outfits, getting ready to leave their respective homes to all meet in one place.

I wished so badly I could get in my car and meet them there. Our Christmas was going to be spent with my parents’ friends — immigrants themselves — in an atmosphere of awkward politeness that usually ended too early in the night. There would be no fireworks to watch, no cacophony of voices as adults drunkenly organized the house to distract the children and allow Santa Claus to leave presents without being seen.

*

I once asked my brothers if they felt lost about home, too.

My brothers are fraternal twins and were six years old when we migrated to the U.S., two and a half years younger than me. I remember starting fourth grade, and crying nearly every morning when my dad dropped me off. I didn’t want to be in a school where I didn’t speak the language, didn’t know anybody, didn’t understand the newest fashion trends. I would make my dad walk me to my classroom, stand in the doorway as I walked in, and stay there as long as possible while I got situated at my desk. I would look back every thirty seconds or so to make sure he was still there. He usually was: his familiar bearded face looking straight at me, smiling and waving. A protector.

I don’t know how long he stood there most mornings. And I don’t know how long we held up that ritual. I remember, after some weeks, my fourth-grade teacher found out I was a Beatles fan and asked me to bring some cassettes with their music. From then on, she played them every morning. Four protectors.

My brothers had it easier adapting to first grade. I used to be jealous of them for this; they seemed to spend their days playing with their classmates, instead of struggling to learn a language and long division mathematics.

But when I asked them about it recently, they told me about their difficult times, too.

One of them, Santi, said he got in trouble in school one day and couldn’t explain he had done nothing wrong because he didn’t have the words to defend himself in English. But he, too, had a generous teacher who allowed him to write his journal entries in Spanish until he felt comfortable enough with English.

The other one, Emi, said he felt disoriented at first. He described it as “kind of like the feeling you get when you’re in a room that’s full of people and there’s a lot of noise, and then you go to a room that’s empty.” We’d gone from a lot of family members and friends to, all of a sudden, just being us five.

“You feel something is missing,” he said, “but you’re not one-hundred percent conscious of what the change is.”

Today, neither of them feel completely at home in the U.S. or in Argentina. But Santi makes a good point: we’ve found home in other things. Home doesn’t need to be a country; it can be a hobby, or a career, or a band.

Home isn’t a physical place, anyway — it’s what ties you to the place that makes it home. It’s about the people that inhabit the space, the language spoken, the food eaten, the traditions kept.

But what if all the things that make me feel at home are spread out across many physical places? Will there always be a piece missing, no matter where I go?

*

The concept of home is something I’ve been obsessed with for most of my life. And I’m thinking about it more than ever, now, after three months of strict home confinement in somebody else’s house and somebody else’s town. After nine months of border closures between Spain and the U.S.

When I think about home, I’m usually led back to my migrant ancestors, wondering if they felt lost or out of place in Argentina.

I ask my mother if her father felt Argentine or Italian. I suppose he’s the closest thing to my experience I could get to: we both left our respective countries when we were children. She says he called himself Argentine and would make mistakes speaking Italian – small things, like verb conjugations. I do the same thing in Spanish. But I’d never call myself American.

I ask my father if his father felt Argentine or Spanish. I already anticipate the answer: Spanish, of course, he was an adult when he migrated. He spoke with a Spanish lisp until he died. My dad says my grandfather romanticized Spain and part of him always wanted to go back. I wonder what that must have felt like, before internet and cell phones. Do you miss less when you’re not constantly reminded of what it is you’re missing?

My mother says the only part of her family that really stuck to their roots were the Irish-Argentines: her mother went to an all-girls Irish school until she was 18, she would get together with her sisters every week for tea time, she would read Argentina’s only English newspaper. I suppose it makes sense: culturally, of all my ancestors, they were the most isolated ones — there’s not a huge Irish community in Argentina, as opposed to Spanish and Italians. And for three generations — that is, until my grandmother — they all married other Irish migrants and worked in the Argentine countryside. They lived in a little Irish bubble within a country mixed with Indigenous people, former enslaved people from various African countries, and newer migrants, mostly Southern European, who acted like they owned the place (and some of them did).

I wonder if they romanticized the Irish countryside, forgetting about the rotting bodies left behind from the Potato Famine (or better said, from England’s refusal to let the Irish eat anything but potatoes). I wonder how they felt, speaking a different language, being around other migrants who spoke other languages. Holding on to the Old Country traditions, and watching their children forget them.

Did they have a sense of home? Or were they too busy working, feeding their dozens of offspring to even think about these things?

Am I only thinking about it because I have too much time on my hands?

I ask my parents: do you feel Argentine or American? They laugh and my mom says: neither. My dad says: Argentine. (“With this accent?”)

*

I never know what to say when people ask me where I’m from.

In the U.S., I used to say: Argentina. Since I moved to Spain, I say: Argentina, but I lived most of my life in the U.S. When I’m traveling, I say: I live in Spain, but I’m from Argentina, but I lived most of my life in the U.S. By the end, I’ve either confused the person I’m speaking with or completely lost their interest.

I’m jealous of people who have a clear sense of identity. Sometimes I think it must make a person more whole, or more confident, or more rooted. It must at least make them less confused when they feel homesick, knowing what home they’re sick for.

I’ve asked my boyfriend many times what it’s like to truly feel Catalan. What is it like to have your entire family in the same town? What is it like to have only Spanish ancestors, as far as you’re aware of anyway? I can’t go back more than two generations without coming across yet another migrant. Even my Italian grandfather had a Swiss-German grandfather. Where does the search for home end?

But sometimes, admittedly, I like having no sense of home, of being a blank slate of sorts. It makes me culturally malleable.

I can go to Ireland and have an excuse to identify with their ways: I, too, like tea time; I, too, hate British imperialism; I, too, love telling folk stories.

I can go to Italy and tell them I’m sort-of-Neapolitan. I walk up and down Via Mergellina in Naples several times imagining my grandfather strolling the street as a child with his siblings and parents. I look up at the Vesuvius volcano and think about all the times my great-grandmother, whose heart broke when she left the city, must have watched that ancient mountain and basked under its protective presence. I see my name everywhere. I see my mother’s maiden name just as often, and reminisce about a long-lost cousin when I meet someone who shares that last name. (Which, to my disappointment, ends up being one of the most popular surnames of the region.)

I can live in Barcelona and bike past my grandfather’s apartment every time I take Passeig de Sant Joan to head downtown. I tell local friends my grandfather was from here and make a used-up comment about making the full migratory circle: from Barcelona, to Buenos Aires, to Texas, back to Barcelona, in just three generations.

But I don’t actually feel like I made a full circle. It doesn’t feel like coming home at all.

*

I left the U.S. because I never felt completely at home there. I thought maybe Spain or Italy — the Mediterranean culture in general — would be more fitting.

I was right, in some ways. Barcelona does feel more like home than Texas. But that alone doesn’t make it a home. I was foolish, maybe, to migrate yet again; how could I find home by leaving everything I had known for the last 18 years? How can moving, constantly, lead me to a home? How quickly can roots grow when I’m on the go, traveling, searching, looking for something? What am I looking for? And why am I looking outside myself?

Sometimes I dream about moving to Naples — it’s the closest I’ve ever gotten to finding a place that feels like Buenos Aires, my original home. The first time I visited, it helped me understand Argentina better: So this is where a lot of our food comes from. So this is why we yell when we speak, why we speak as much with our hands as with our mouths. So this is where lottery traditions like la quiniela come from.

But I know, now, that moving to Naples would be chasing an illusion.

*

If I’m told one more time that “you find home within yourself,” I’m going to scream until my lungs are flattened without air.

*

Another option: accepting the feeling of not having a home. Living with the always-present emptiness; sometimes it’s big, sometimes it’s small. Sometimes I cry all day because of it. Sometimes I barely notice it at all.

Next time someone asks, I could say: I have multiple homes.

But this isn’t quite right either. I don’t feel stretched out across many homes; I feel like I have little snippets of home in many places, none of which fully feel like home. None of them could ever be.

Maybe, leaving your country (or countries) is like surviving a death. You never get over it; its presence, the hollowed space it left behind, is always there. You just learn to live with it. And some years are harder than others.

Lucía Benavides

Lucía Benavides is a journalist and writer based in Barcelona, Spain. Originally from Argentina, she was raised in Texas from a young age. She has years of experience in international reporting, feature writing and radio producing. She also writes short stories and essays.

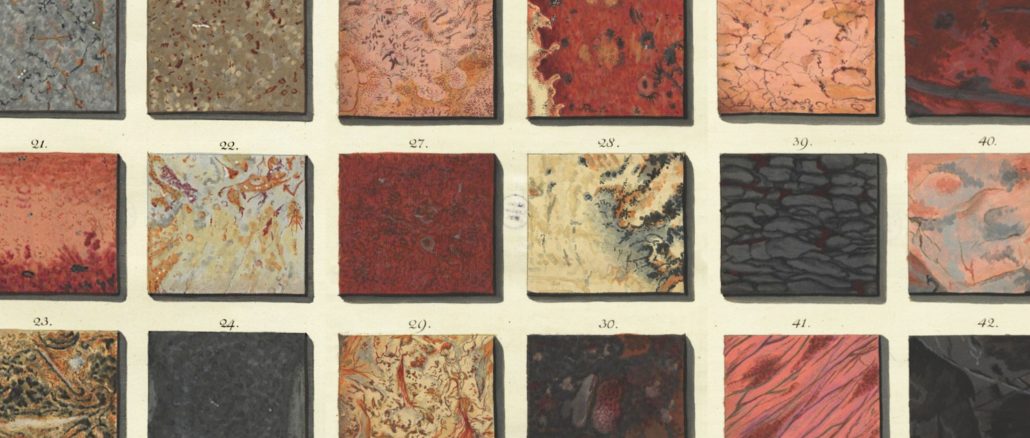

Featured image: Artwork by Adam Wirsing on The Public Domain Review.