“Cheers!” he shoved a cold Heineken in my hand as soon as I arrived at his home, the one-thousand-square-foot house hidden in a jungle of persimmon and fig trees in a relatively undeveloped flood zone in Santa Clara. I came to celebrate my kid brother‘s thirty years of living in America and his fifth-fifth birthday. Brother Hải is number four in the line-up and two years younger than me. We are seven brothers and all of our names begin with H.

His thick black hair had turned a shocking white because he had skipped coloring it for two weeks, but at least he still had all of it. Somehow, I did not inherit that gene on my mother’s side. Some say stress did it, but I think living well could, too.

He sat comfortably cross-legged on his threadbare, brown, corduroy couch with a beer in his hand, talking slowly in a low voice, “You know, I have lived here longer than in Vietnam.”

“Me too,” I nodded. “I’ve spent most of my adult life going to school, working, doing just about anything to make a living, fitting in, becoming American.”

Watercolor and oil paintings of scenes from Vietnam decorated his walls. One was a papaya plant bearing large swollen fruits, a palette of green and yellow. Against the pale green background, the largest fruit was ripening like a woman’s breast, heavy with milk. Next to the papaya painting was one with a rooster crowing, beak held high, his back arched in a fluid curve flowing into his shiny green tail feathers. A hen and her chicks kept their heads down, hammering the ground. She scratched for worms stirring up dry dust.

The one I love the most is a large square of dark green, blue, gray, a mix of the darkest colors, somber like a funeral home. If one looks carefully in the lower right-hand corner, a small lance-shaped object, like a falling bamboo leaf, seems like the painter’s errant stroke or an oversight, something that should not be there—something that was tossed about, totally lost in a stormy sea.

He had sold a number of paintings and kept some. I had helped him sell and even bought a few of his paintings when I knew he needed the money. I wanted to buy that dark painting, “The Boat,” but I knew he would never sell it to anyone. Not even to me and that’s why I never asked. One day, I want his daughters to have it.

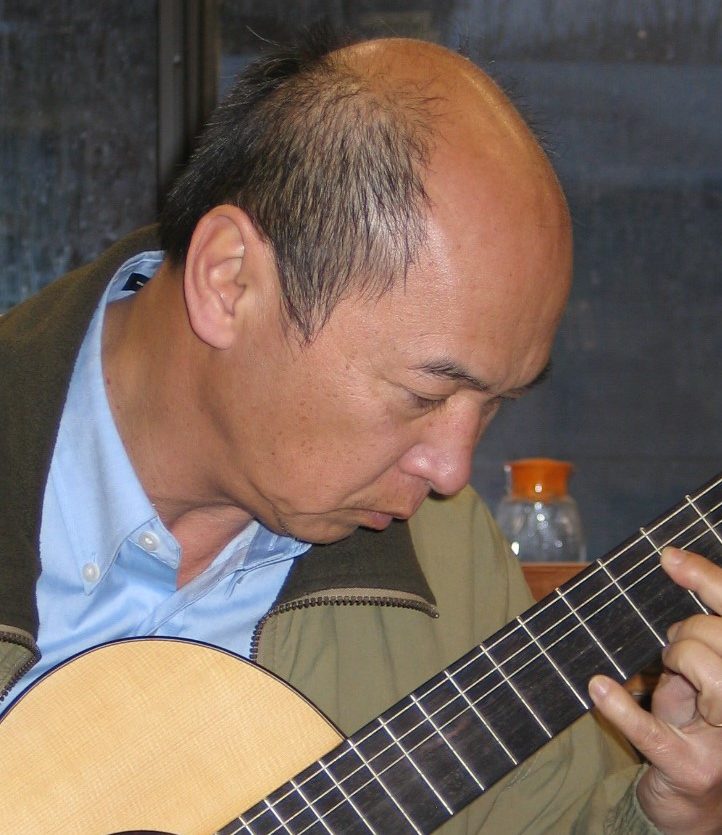

Without any formal education in arts, he turned out beautiful watercolors, black and white charcoal, pastel, even oil paintings; my brother has a true gift. He’s also collected and played many musical instruments, from the harmonica to violin, all self-taught, but painting is his passion. At one time, he rented a stall at the San Jose flea market and did portraits for five bucks apiece. Then after he got married, he put away his brushes and easel and applied for a regular job in a computer company as an engineer.

“I don’t need much money for myself,” he used to tell me. “I can live on very little and I could survive as an artist. Years of living in the new economic zone, I ate sweet potatoes and boiled leaves day in and day out. They are inexpensive and good for me.” Eating very little meat is a habit that he maintains even today. He gave me long explanations about why he chose the potato diet, “People are originally starch eaters. If you don’t eat greasy foods, your body doesn’t have to work hard to digest and you don’t get sick.” He tried to convince me to change to his minimalist lifestyle.

Thirty years before, he arrived at San Francisco International Airport with his only possessions: a pair of rubber flip-flops, the threadbare clothes he was wearing, and a Red Cross plastic bag that held a toothbrush and an extra pair of shorts.

I had not seen my brother for almost ten years since the day I left my family to go overseas on a scholarship about one year before Sai Gon fell. He was just a boy of fifteen and wanted to follow in my footsteps: take English classes and go to college in a safe country. But then Giải Phóng happened and he never had the chance. All my younger brothers are the products of the new regime.

When he arrived at SFO, his black hair had sun-bleached into a reddish brown and his lean but muscular body could pass as a day laborer. However, his leathery skin, heavily calloused hands and dirty fingernails could not hide the inherited fine bone structure—not meant for farm work. Our ancestors had spent years in classrooms and passed exams to become mandarins and government officials to avoid working in the field. My brother must have been the first one in a long family lineage who actually worked with his hands to feed himself.

He smiled self-consciously with a missing front tooth when he saw me waiting at SFO in my bright red knit shirt with a green alligator logo.

“Anh Hao! I am so happy to see you. I am so happy you are here. I am totally lost…” He shook like a wet bird when we embraced. He looked around, over his shoulder, left and right, spooked by all the bright airport lights, well-stocked gift shops and fast-walking, well-dressed travelers.

“Do you have a cigarette?” he asked.

I shook my head no.

“I need a smoke fast and I don’t have any money.”

On the drive back to my apartment, I stopped at a 7-Eleven and bought a pack of Marlboros, the red pack that he preferred.

Right in the parking lot, he broke off the filter, inhaled the first cigarette, and then lit another. He offered me one. I shook my head.

“In Vietnam, everyone smokes, even kids. I am addicted.”

After the third cigarette, he relaxed and smiled again with a half-open mouth, conscious of his stained and decaying teeth. “Thank you for the smokes, the best I had in years. I smoked everything I could find, corn stover, tobacco smuggled in from Laos, very strong!”

Even after thirty years of living in the anti-smoking state of California, he still can’t kick the habit. He would sneak out to the back of his house to avoid his wife and the girls. His daughters would make faces when they saw him smoke, “Yuk!” He tried the patch, cold turkey, and smokeless tobacco without success, but he has cut way down because of rising costs of heavily taxed cigarettes.

I had first known of his intention to escape Vietnam when I received a letter from my mother: “Your brothers want to leave the farm and go live with Uncle Minh in the central highlands.” We had no Uncle Minh who lived in the highlands; we didn’t even have an Uncle Minh!

I wrote back: “I hope they will make it to the highlands. It is colder but they can grow many vegetables there. I will send some money to pay for the long journey.”

At the time, I was a new immigrant in the U.S. I went to San Francisco City College during the day and worked as a dishwasher at the Vietnam France Restaurant at night. At the corner of Divisadero and Bush Street, the restaurant was a family-owned business that would seat about fifty customers at capacity and with about two or three turnovers each night; we served more than a hundred clients with delicious and inexpensive dinners. Vietnamese cuisine involves a lot of dishes: Large, small, sauce dishes, bowls, spoons, forks, and chopsticks. All had to be sorted. All had to be scraped and washed.

About four hours each night, I stood at the large metal sink with a plastic scraper and pushed morsels of rice and leftovers into the garbage can. Then I squeezed the power sprayer to blast away the scraps before loading the dishes into plastic trays and shoving them in the stainless-steel industrial washer. My plastic apron was coated with the washing spray and the bleach ate away at my pants. The grease and chlorine soaked through my skin and hair, and I smelled of fish sauce all day and night.

When the dinner rush died down, the staff sat down around the table in the back. Mr. Nam usually saved me a dish that someone returned to the kitchen. Wrong order, something like that. A succulent piece of Duck l’Orange or Chicken Cordon Bleu. Always his trademark, he added a round ball of rice and a serving of stir-fried, shredded cabbage in garlic and scrambled eggs.

Mr. Nam lived alone, above the restaurant. He only came down to cook and went back up to sleep. The restaurant was open six days a week and closed on Tuesdays. He had no car and no friends. He had a family in France, but he didn’t want to talk about them. I found that he knew a lot about whiskeys and French literature. He mentioned occasionally that he used to work for the last Prince Bảo Đại of Vietnam before the last royal family were exiled to France. He helped me send letters and money to my family in Vietnam.

Sending letters to and from Vietnam back then was like smuggling drugs. It usually took about one week to get a letter to an acquaintance in France and another two to three weeks to forward it from Paris to Vietnam. Sometimes, letters didn’t make their way there at all—they either got lost along the way or were opened and censored somewhere in a dark, damp office of the political police in Vietnam.

Sending money home then was even more difficult because there was no legitimate way. Because Vietnamese piasters were worthless at an inflation rate of over a hundred percent a year, rich people hoarded gold and tried to transfer their wealth to a foreign country where they would eventually go. Thus, a smuggling business was born. It worked like this: You give money to a gold merchant in America or France in dollars. They usually had connections and could navigate any corrupt government and underground markets. They told their relatives in Vietnam to deliver the gold to your family there — the result was a net flow of money out of Vietnam at great profits for the money dealers.

Since I got news of my brothers going to the central highlands to live with uncle Minh, I opened my mailbox many times every day anxious for news. Nothing came from my mother for about six months and then finally a letter, “Uncle Minh died, so your brothers came back to the farm.” So, their plan to escape failed. I later found that the escapees got as far as the cape of Cà Mau and the Việt Cộng coastguard sprayed AK-47 bullets at their boat. They jumped in the river and swam like rats as the boat sank. Somehow, they managed to stay alive and out of trouble for a while, but I had no idea what they did for months to survive. I stopped hoping to see any of them again.

And then one day, another telegram came to my apartment from my oldest brother Hoan, “We are in Pilau Bidong, Malaysia. Please get us out.” My oldest brother, his wife, and my kid brother had made it to a refugee camp after all. How did they do it? They crossed an ocean and survived! That day, I broke open a bottle of Jack Daniel that I had saved for a special occasion and drank a few shots. Usually, I never drank alone, but that whiskey went down smooth. They had joined a hundred refugees packed in a thirty-foot boat, all trusting their lives to various gods. In the darkness, they slipped out into the ocean. After two days, the old motor quit running. They didn’t bother rowing because they did not know which way was better: north, south, or east? North, they might find Hong Kong; south, maybe Malaysia, the Philippines; east, God knows what. The U.S. had stopped picking up refugees after the first year following the fall of Sai Gon in 1975. They didn’t expect to be rescued by anyone. The boat of people just hoped their vessel would hold up long enough for the journey, and hit land somewhere without them running into pirates in the gulf of Thailand.

Their three-day trip turned into twelve days of drifting. Water and food ran out on the sixth day. They floated with the trade winds southward in the open sea. They prayed for other boats and wished to die quickly if pirates found them first. There was nothing to do but pray.

“After we ran out of fresh water and food,” my brother explained, “people had to cook whatever was left and everything was salty. Someone found a piece of moldy bread on the floor and we shared it. I still remember how good it tasted.”

At last, a large wooden boat approached them from behind like pirate ships usually do. Everyone braced themselves. The men on the large boat yelled loudly, but my brother couldn’t tell what they wanted. The refugees hunkered down waiting for the assault to begin. After a few minutes of standoff, the seamen threw over a rope for the refugees to catch. They passed down plastic jugs of water and rice wrapped in banana leaves and then towed the refugees’ boat to a small deserted island and cut it loose. Glad for being saved from sure death, the refugees thanked the fishermen with a few ounces of gold they had hidden in the motor.

My brothers Hoan and Hải and other refugees ate bats, snails, and mud crabs. They collected fresh water dripping in caves. Within a few days, another boat arrived from the Red Cross and took them to Pulau Bidong, the refugee camp in Malaysia. My brothers lived with thousands of refugees on the beach of Pulau, waiting for me to sponsor them to come to the U.S.

In California, my two brothers enrolled in De Anza Community College, learned English, and worked every menial job to pay their way through San Jose State. The timing was excellent for literate Vietnamese refugees to enter the booming high-tech job market in the Silicon Valley. They rode that wave.

“So brother, tell me your plans, what are you going to do next?” I asked just to get him to say something.

“I want to buy some land in Gilroy, an acre, maybe two. I want to start a farm,” he squeezed his hands together. “I always love the land, the feel of clay and sand between my fingers and the brown worms that make the earth good. They are the real workers, you know?”

“How about Silicon Valley? Is there a management job for you?” I asked.

“There is not much for me here in the high-tech industry. I am getting too old to be competitive. Look around. Everyone my age is being laid off. The jobs are going overseas. The new hires are younger and cheaper and have to compete with bright kids from all over the world. Next stop is unemployment. Early retirement,” he smiled ironically.

Then his eyes lit up.

“I was the only one in the village who could read, write, and do simple math. I had an important job: keeping track of supplies and rations for the cooperative. I was only sixteen but I had responsibilities over twenty families who trusted me. They even wanted me to marry their daughters. Imagine that!” he smiled.

“There was this street vendor who really liked me, I could tell. She used to sell rice porridge in the morning and sweet chè in the evening. I liked her too, but I was too shy to say anything, you know? I just didn’t know what to say to girls. Of course, I couldn’t tell anyone that I was planning to escape; I couldn’t tell her either. One night, as we sat in the dark watching the stars, she took my hand and placed it on her breasts and asked me if I found them soft. I didn’t respond and she cried. I suppose by now, she would have been married to a farmer and had a bunch of kids.”

He quickly changed the subject to the computer gadgets that he tested, the lay-offs in his company, his worries about the mortgage and the two girls who grew up fast with needs for dental braces and designer jeans. He dismissed all his work and daily life activities as deadly boring and the reason he worked at all was to provide for his wife and daughters.

“Brother Hải, tell me the truth. After having lived and done so many things, what have been your best memories?” I asked.

After a short pause, he sighed, “I often think about Tây Ninh. We were hungry when our father was sent to a jungle camp up north and you were gone and I grew up in a hurry. Brother Hoan was also in re-education for his army service. Brother Hưng went to Cambodia with the youth volunteer army. I became the oldest of the litter so, I kept Ma and our younger brothers alive for years with my own hands. I made decisions for the family and sometimes for the whole village. I learned by doing. I changed a forest to a farm. I cut down trees, built a house, and dug canals to bring water from the river to the farm to grow rice and manioc. I learned to lead by example, by sacrifice, by gaining people’s trust and respect. I was a leader, you know?”

“What’s different now?” I asked.

“Here in the Silicon Valley, I am one of a few hundred thousand computer engineers, all with degrees from someplace. Sure, I rode the high-tech wave when I came here but that wave has long passed. When I look around, most of us have been laid off. I am among those to go next. “

“Oh, then another highlight of my life — you wouldn’t believe it — was Pulau Bidong. I helped the illiterate folks with their paperwork, applications, and letters to their families in exchange for cigarettes. The Red Cross fed us mackerel, SPAM, and canned beans. In the afternoon, I went swimming in the warm ocean. Camp Bidong had one of the most beautiful beaches in the world. I would love to see it again one day. What more do you want? Work, eat, and go to the beach! Better than starving in a stinking boat—better than testing electronic circuits every day.”

“Why don’t we do it one day, just you and me. We can go back to Vietnam together, go visit the farm, to the place where you set out to sea, to Pilau Bidong, just you and me?” I said.

“Brother, thank you for what you did for me,” I grunted something, knowing what he was going to say.

“Without you, there is no me,” he continued. “Do you remember the ounce of gold?”

“No big deal brother. I wish I could do more.”

“It changed my life forever.”

“I was fifteen years old when our father went to re-education camp up north and mother had to sell all we had to feed us. That lasted about one year and being desperate, we followed the government’s order to leave our place in Sai Gon and go to Tây Ninh near the Cambodian border. They gave us a plot of forest to farm in the new economic zone. Ma needed me to be strong to do farm work. We lost touch with you for so many years before you found us again through Mr. Nam and his contacts in France.”

“Then one day Ma made me go. She saw me read a book one evening by the kerosene lamp, a classic literature book that didn’t get eaten by the termites. Something happened in her head and the next day she gave me the gold and told me to go. She said that being a farmer was not for me and I needed to go join you in America. I told her I wanted to stay, but she told me that my job was done there and the village would be fine without me.”

“Brother Hoan and his wife had arranged for everything and they told me to join them with the escape plan. They told me to tell no one but our mother. The morning I left the village, I waited outside for the bus to get to the city. Little brother Hiền came out to see what I was doing and I hugged him for a long time. Somehow, he could tell that I was saying good-bye. He ran after the bus until he couldn’t run any more. I saw him collapse in the red dust and diesel exhaust.”

In 1980, gold was eight hundred and fifty dollars an ounce, an all-time high back then, perhaps because of all the smuggling to and from Vietnam. It was also the going price for a place on one of these refugee boats. I was still a student and a dishwasher in a small restaurant in San Francisco so I had no savings. I borrowed and scrounged enough for three ounces and Ma decided that one ounce was to buy him a chance for a future. He became one of the boat people — hundreds of thousands who bought and stole their way out of the country in unsafe vessels, trusting their lives to the sea, tossed about like a bamboo leaf in a storm.

I often wonder about all the scenarios that could have happened to my brothers. What if they never came to America? What would happen to my sister-in-law if they were captured by the pirates? What if they drowned and died in the South China Sea and I would spend the rest of my life regretting my role in this plot? What if I had done nothing?

I often think about what that ounce of gold had bought. It gave me so many years of having my kid brother with me and watching his daughters grow. I would willingly pay many times more than that for the privilege. I hope his life here has been fulfilling and sometimes I have my doubts, but then who is to judge? My nieces have the opportunity to live their American dream. My brother and I can get together once in a while to share a beer and talk about where we came from. That alone is comforting enough for me.

“Coming here to America is really all about the next generation and the opportunities for the kids who are born here. We are a lost generation — you and me. We straddle the ocean. Our bodies are here but our thoughts are there. We are not whole, only halves,” he stuck another cold Heineken in my hand.

Hao Tran

Hao left Vietnam as a young man to go to college in Australia in 1973 and later settled in the United States. Shortly after he left Saigon, the war ended and he couldn’t return for twenty years. Since 1994, he has come back to his homeland a dozen times and many of his short stories are based on his journeys.

Hao Tran’s stories are from the perspective of a Việt Kiều—a Vietnamese living overseas. He writes about his own experience as an immigrant, the lives of those closest to him, the people he encountered in his travels, and the dramatic and heart-breaking changes in a post-war Vietnam.