There are over 45 million “Colombians” living within the country’s borders and about 5 million abroad. I am said to fall under the latter category. However, of these 50+ million individuals, can we really sit down and agree on a set of characteristics to essentialize what it means to be a Colombian?

Though it seems easy enough for those who consider themselves Colombian, once challenged to unpack what it means most will recognize there are inherent limitations to this endeavor as there are any time one tries to essentialize anything. In the process of trying to construct an identity, one always leaves something out when trying to include something else.

Am I Colombian if I don’t eat bandeja Paisa since I’m a vegetarian? Am I Colombian if I am an atheist and over 90% of Colombians believe in some kind of deity (mostly of the Roman Catholic variety)? Am I Colombian if I am against bull fighting because of its inherent animal cruelty for the sake of human entertainment? What if I am for gay marriage, stem cell research, and abortion? Am I Colombian if I find aguardiente disgusting and I don’t drink coffee? What if I can’t dance cumbia? What if I am against both Uribe and the FARC?

Or, do I just have to be born within the county’s borders, regardless of my opinions on the issues delineated above? I was born in Medellín, Antioquia, but am I a Paisa? I have only lived in Colombia for about third of my life. I speak Spanish but am not considered by home-grown “Colombians” as one of “them” because I have been away for too long and have gathered different experiences “they” don’t share. Sometimes, I am considered a gringo, but in the United States, I am occasionally regarded as a spic or an alien. I am a stranger in my homeland, and everywhere else I have lived (U.S., Canada, Chile, and Japan) I am not identified as one of them, either. In fact, racist comments aside, I am mostly regarded as “Colombian” abroad, even though I now also have a U.S. passport.

How about our blood? Is there really such a thing as being 100% Colombian? If anything, the Amerindians of pre-Columbian Colombia may have been closer to this than us, but even they were descendants of indigenous peoples who migrated south from Asia and Central and North America. Where do we draw the line?

Post-colonialism, the genetic make-up of what it means to be a Colombian has also been mixed with European and West African blood and the genes from others who have immigrated to the territory. We also have to recognize much Spanish blood, for example, is not just European, but also Middle Eastern and North African. All one must do is study the great wars of the Iberian Peninsula, the region, and their migrants, of the last 2,000+ years, to trace the lineage of much of Colombia’s ancestors. This may explain why others have many times assumed me indigenous, Mediterranean, and Middle Eastern. Understanding such genetic history, it becomes difficult to suggest there is such a thing as someone who is 100% Colombian. In the process of trying to construct this identity, we are sure to leave someone out.

When I left Medellín as a child during the violent years of Pablo Escobar’s total war against the government, I was transplanted to a new country without knowing the culture or language. My sister and I were two of fewer than a handful of students who spoke Spanish in our new school. Being thrown into this new world, I, like many who may have shared the experience, searched for an identity. I adopted “Colombian.” Nevertheless, for the sake of staying under the radar, the name on my Colombian birth certificate became anglicized and shortened from four names to two. “You’re no longer Julián Esteban Torres López, but [insert American English accent here] Julian Torres,” I remember my father telling me this when we left Colombia and tried to survive as “illegal aliens” for over a decade.

With Colombia’s tainted international reputation, I was bombarded by the essentialization of “Colombians” from “non-Colombians.” Every chance I got, I took the opportunity to challenge their stereotypes and prejudices: “No, my father is not a drug dealer … No, we actually do have paved roads … No, I don’t drink coffee … No, I’ve never killed anybody.” In the U.S., I became an ambassador for Colombia and “Colombians” as an adolescent. Hollywood and the news made it difficult to grow up without being negatively portrayed by those who had never met me or “my people.” As an adult, I’ve come to realize that this unwanted ambassadorship led me to become a scholar in Colombian culture, politics, and history.

As I spoke with other immigrants around the world, I became aware we shared a similar experience. We tended to feel more “Colombian” than possibly those living back home. What exactly that meant, I don’t know. We, in a way, embraced other stereotypes of what a “Colombian” supposed to be. This may have been due to the fear of losing one’s language, traditions, and culture while abroad, which led us to cling on to that abstract and somewhat imaginary identity maybe stronger than non-immigrants. For a while in my 20s, I even tried to name myself and claim myself—as Khalil Gibran once wrote—by readopting my Spanish name in pronunciation, spelling, and number of given names. This confused my friends, and, though satisfied me for a while, still left an emptiness inside because, as I have come to realize, I am more than just the X identity I tried to be. Instead of toeing the line of some abstract notion, I was who I was: a hybrid, mixed.

It was not until last year, when a friend asked me the following questions, that I began to really dissect my identity: “Are you proud to be a Colombian? Are you proud of Colombia?” I don’t recall my exact answer, but I have since meditated heavily on this topic. Though for years I was a self-proclaimed ambassador for Colombia and Colombians, I quickly realized I was not in standing to answer such questions. Could I really take praise or blame for what Colombians have done, good or bad?

Maybe we cannot sit down and come up with a list of characteristics that essentializes 50+ million people. Maybe it is more like Ludwig Wittgenstein’s idea of family resemblance: there is no one characteristic we all share, but if studied as a group we can conclude we are most definitely related. Or, maybe it is like what the U.S. Supreme Court says about pornography: though we can’t agree on one definition, we know it when we see it.

All I know is that in three decades of reflecting on my so-called identity, I have come to accept that answering the question guiding this discussion on what it means to be Colombian is both personal and communal in nature. There seems to be a need or want to define others and ourselves to more effectively realize the lives we wish to lead as individuals and as collectives. Further, the answers seem to suggest it is not a black or white issue. There’s a continuum, a liminal space, where all of us fall between the affirmative YES and the affirmative NO. It is in this arena where “boundaries dissolve a little and we stand there, on the threshold, getting ourselves ready to move across the limits of what we were into what we are to be.”

My identity is a hybrid cluster of my own experiences. Friedrich Nietzsche may have said it best when he wrote, in Thus Spoke Zarathustra: A Book for All and None, the following:

I am a wanderer and mountain climber,

he said to his heart,

I do not love the plains,

and it seems I cannot sit still for long.

And whatever may still overtake me as fate and experience—

it will be a wandering and a mountain climbing;

in the end one experiences only oneself.

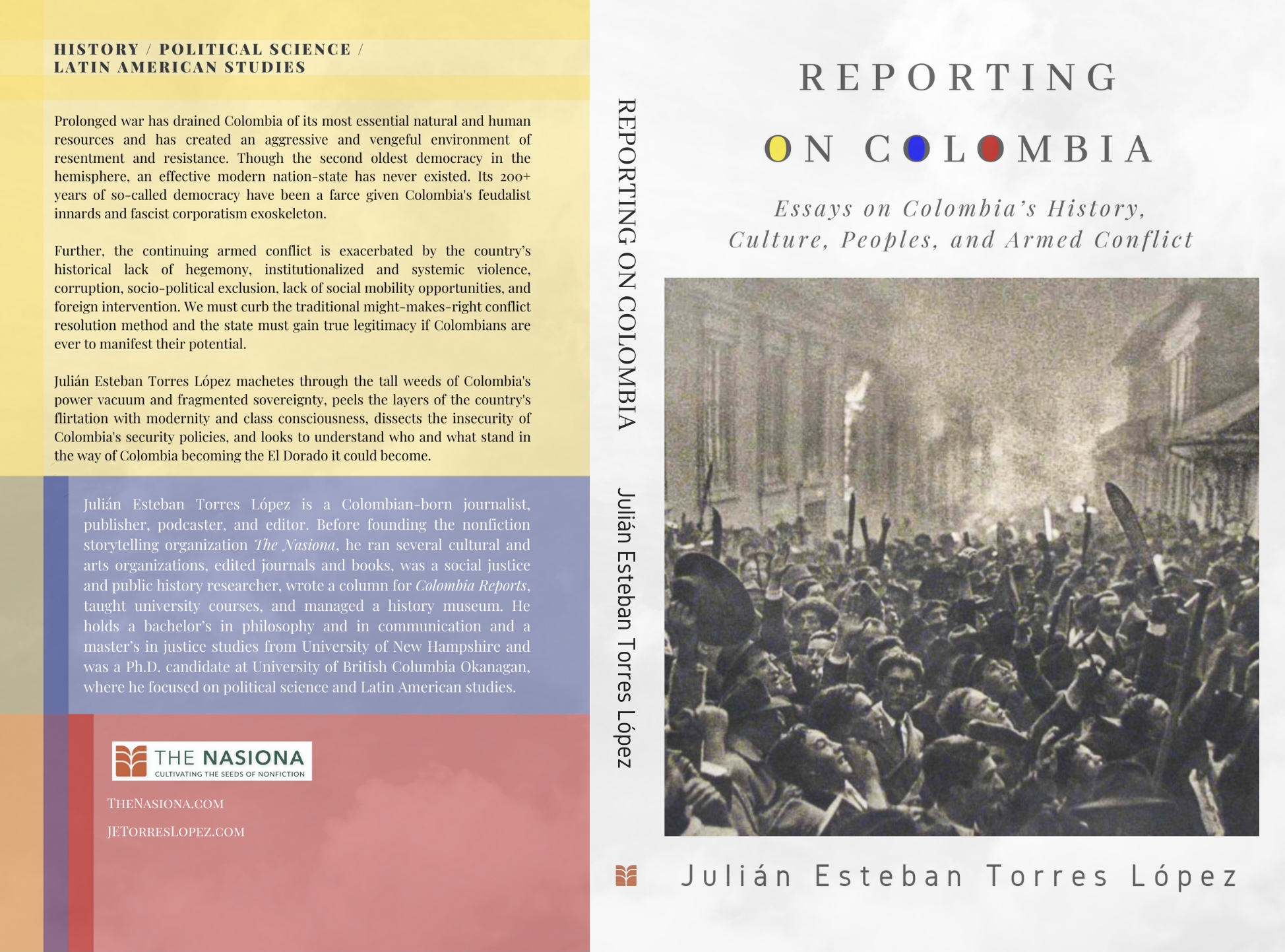

I originally published an earlier version of this essay in 2010 in Colombia Reports. You can read the revised version and 17 other essays in my 2020 book Reporting on Colombia: Essays on Colombia’s History, Culture, Peoples, and Armed Conflict.

Product details

- Publisher : The Nasiona (February 17, 2020)

- Language : English

- Paperback : 222 pages

- ISBN-10 : 1950124061

- ISBN-13 : 978-1950124060

- Item Weight : 10.7 ounces

- Dimensions : 6 x 0.5 x 9 inches

Julián Esteban Torres López (he/him/his/él) is a bilingual, Colombia-born storyteller, public scholar, and culture architect with Afro-Euro-Indigenous roots. For two decades, Julián has worked toward humanizing those Othered by oppressive systems and dominant cultures. He is the creator of the social justice storytelling movement The Nasiona, where he also hosts and produces The Nasiona Podcast. He’s a Pushcart Prize, Best of the Net, and Best Small Fictions nominee; a Trilogy Award in Short Fiction finalist; a McNair Fellow; and the author of Marx’s Humanism and Its Limits and Reporting On Colombia. His poetry collection, Ninety-Two Surgically Enhanced Mannequins, is available now. His work appears in PANK Magazine, Into the Void Magazine, The Acentos Review, Novus Literary and Arts Journal, Havik 2021: Inside Brilliance, among others. Julián is also a senior DEI consultant for Conscious Thrive Consulting. Julián holds a bachelor’s in philosophy and in communication and a master’s in justice studies from the University of New Hampshire and was a Ph.D. candidate at the University of British Columbia Okanagan, where he focused on political science and Latin American studies.