Stories are the foundation of our civilizations and our societies. Our legends and myths, our scientific discoveries and our explorations, can inform and influence us both individually and collectively. But what separates us also holds us together. What divides can inspire unity, and through story we discover our belonging.

It is through story that we discover our connections that span like a great bridge, both distances and differences. It is through story that societal change takes root and scientific and technological advances are conceived. Humans are the only creatures on earth that tell stories. Stories are like mirrors where we can view ourselves, both who we have been and who we might become. From the Epic of Gilgamesh to Hamlet, to Harry Potter and thousands more, we can recognize ourselves and others most easily through narrative. The collective story of what it means to be human and how we should treat one another is the foundation upon which our cultures, our religions, our rituals, and even our identities are predicated upon. Stories are the bedrock of civilizations and the mortar between societies. While there is much diversity among humans, it is through our shared story that we find mutual understanding and cooperation. It is also through stories that we create wars, incite violence against each other, and isolate ourselves from others’ suffering. Stories bind us to each other, and we can be bonded as easily by hatred as by love through a shared story. And when our hostility, our judgment, and misunderstandings cause us to battle each other, we still end up tethered to one another by the story of that conflict.

As a young person, my contact with stories had been somewhat limited and definitely constricted to the religious stories of Mormon Fundamentalism. But the mythology and the belief system that bound me to the other people sitting in church with me on Sundays was also the story of condemnation and isolation that separated me from the rest of the world. It also caused me to cling to that slim outcropping of my cultural beliefs. I was encouraged to read only the religious books and to study the tenets of polygamy. So I read the Book of Mormon and the Bible, the history of the Mormon Church, the diaries of the early pioneers, and the handmade tracts published by the leaders of the polygamous group to which my family belonged. I read all the books I was supposed to read and still I hungered for more. I browsed a set of outdated encyclopedias, read and reread the same stack of National Geographic magazines, even found interesting information in an old, faded green Fannie Farmer Cookbook. And then I discovered the newspaper. I was not forbidden to read it, but my mother, in particular, seemed distressed by my interest in the newspaper. I realize now that my mother knew something I did not know. That the stories I read in the newspaper might lure me away from my culture and religion. She was wise to be worried.

But I had no desire to leave my culture or my family despite the abusive circumstances of my childhood. I didn’t want to become part of the outside world. I only wanted the outside world to become a part of me. I wanted to bring the forbidden inside. Reading the newspaper brought all the events and ideas that were out there, and delivered them like the Trojan horse, to the driveway at three o’clock every afternoon. I made a regular habit of sneaking out the front gates right as it was delivered before anyone saw it and stealing it. I slid it under my dress and secured it in the waistband of my underwear and went back into the house, careful not to bend it. When I was safely in a bathroom with the door locked, there I would read it, and upon finishing, refold it, slip the elastic band around its middle, and return it, just as sneakily, to the driveway with no one the wiser.

I read every section of the newspaper with equal interest—world and local news, sports and arts, movie summaries and TV programming, comics, editorials, opinions, advertisements, and obituaries. I read about the space shuttle Challenger exploding, the meltdown at Chernobyl, the US Gymnastics team of the 1984 Summer Olympics, and all about the latest Tom Cruise film. I could talk about Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev as if I knew them personally. I laughed out loud at Dave Barry’s humor column and read each and every comic strip, saving the Far Side, by Gary Larsen, for last because it was always the best one. The whole world could be accessed sitting on the edge of the tub in the bathroom. Every evening after my father had read the paper, I gathered up the sections that interested me most and tucked them in the back of my closet for rereading later. When my newspapers became wrinkled and worn, I pulled out the ironing board and freshened them up with a good pressing. But my family had limits to how much of this invasion would be tolerated. When my mother found my stash of newspapers and insisted I throw them out, I hid them better, instead.

During my teenage years, I became a sports fanatic. Not because I particularly loved sports but because I read the sports section of the newspaper so consistently that I knew the names and stats of the entire NFL, NCAA, and NBA. All this knowledge allowed me to talk sports like a bona fide enthusiast. I had even convinced myself. I watched the games on TV with my father who enjoyed sports for their own sake but especially liked basketball. And when Utah acquired its first professional basketball team, the Utah Jazz, he followed their rise to prominence with enthusiasm. The year I turned thirteen, he purchased a new car, and with it he had been given two season tickets for all home games for the Utah Jazz. All of the kids were given the rare treat of going with our father to one of the games. My game was against the Dallas Mavericks. It was the first time in memory that I went somewhere alone with my father. But more than that, I wasn’t confined to reading about this basketball game, I was going out into the world to live it.

We arrived at the Salt Palace Arena and found our seats. The noise, the pressing crowd around me, the smell of hot dogs and popcorn gave me a buzz of excitement. The teams were evenly matched, and we were both on the edges of our seats throughout the game.

“This is a lot better than watching it on the TV at home, yeah?” Father asked elbowing me playfully. At halftime he leaned forward to look down at the court below us, tapping his hands on his thighs in time to the music. Cheerleaders were dancing and doing stunts; the music was playing so loudly I could hardly hear Father’s voice. “You want a hot dog? I want a hot dog.” It was a bit surreal seeing Father like this. This was not the father that tugged gently at my braid while I was doing the dishes and asked me if I had been a good girl. Or the one that came downstairs on Saturday night in his serious suit and tie, carrying his scriptures in his hands and smelling like aftershave. And it was definitely not the father that sat in the armchair during Sunday School, wearing his authority in the furrows of his bent brows.

“It’s not looking good for the Jazz,” Father said, when the fourth quarter was nearly over. They were behind by seven points with only thirty seconds of game time left when they called a timeout. It looked like the Mav’s had won it. The stadium began to empty. Father asked me if I wanted to go home. The Jazz had lost. I said, no. I wanted to stay and cheer them on to the last second.

“We oughta go home, get ahead of traffic.” He stood up.

“It’s not over ’til it’s over. They might win yet,” I said grinning and staying firmly in my seat.

Father laughed and sat back down. “Well, if you say so.”

And so we stayed those last thirty seconds. The Jazz rallied but were still behind by two points. With just three seconds on the clock, they intercepted the ball and tossed it to their shooting guard who took a jump shot at thirty-three feet from the hoop. The buzzer rang. The game was over with the ball still arcing through the air and time slowed down, those still left in the stadium grew quiet, everyone holding their breath. I can still see the shooting guard, suspended in the air, shoes hanging, arms extended high, hands surrendered. And then the sound of the ball as it swished through the net, without touching the rim. The stadium exploded. Father jumped out of his seat, yelling and pumping his fist into the air. I was hollering, too. Everyone was up, hands in the air, whooping and cheering. The sound was deafening even though so many people had already left. I started to cry.

The cheering died down and we left our seats, but we rode the electric energy of the crowd that carried us forward in a sea of people; not just any people, but our people, other Jazz fans, all of us stepping out into the cold November night. And my father spoke casually to the strangers who were nearest us, who were no longer strange but had become our brothers and sisters of basketball. It was the story that allowed us to suddenly trust each other. During the drive home, he couldn’t stop talking about that jump shot. “The comeback of the century,” he called it. I still had a lump in my throat. Father laughed again and slapped his thigh in disbelief.

On that night, in that arena, the man sitting next to me was not my father. He didn’t behave like my father or even sound like my father. He was a fan. Just like me. And I felt more connected and bonded with him that day than I felt ever before or again. Together we experienced the thrill of that win, the excitement of the final seconds, and the bated breath of the still thousands of us remaining in the stadium. We were equals that day, my father and me, the story had made us the same. But we were also one with the crowd. The outside world had found its way inside of me.

Even the smallest stories have power, and the best stories bring us together by reminding us the ways in which we are inextricably connected and inexorably drawn to each other. Even when the distance between two people, two cultures, two divergent paths seems too vast, the story that we stand on is vaster. Empires rise and fall, cultures and even languages are lost, civilizations progress, and beneath it all is the story of us, all of us.

The next morning at the breakfast table, he gave a rousing rendition of the last thirty seconds of the game. “Tell them, Susanna,” he had said when he was finished, as if no one believed him.

SUSANNA BARLOW is a full-time writer. Her memoir Not in My House is about her life in a polygamous family and how she overcame the struggle of surviving abuse. It won First Place for Creative Nonfiction in the Utah Original Writing Competition 2017. An excerpt of her book was published in Artists of Utah 15 Bytes in 2018. She enjoys helping other writers with one-on-one writing guidance and as a developmental editor. You can find her online at susannabarlow.com and on Twitter.

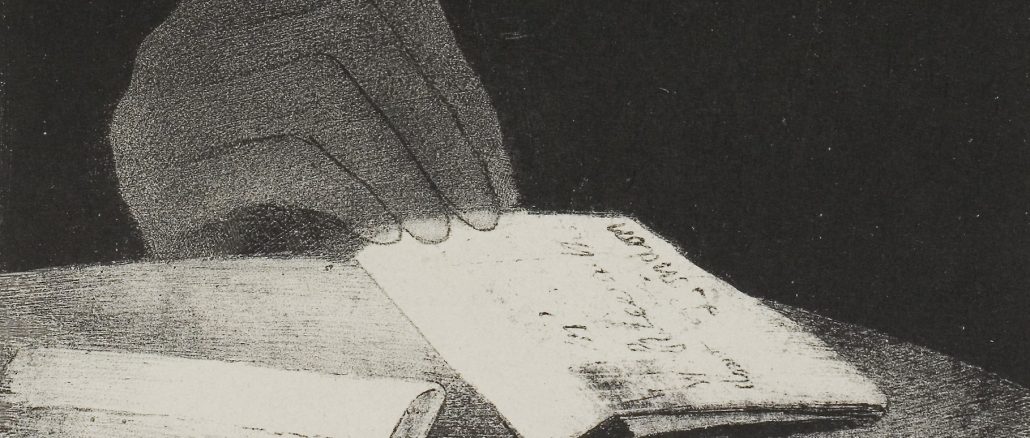

Featured image: Odilon Redon, “It Was a Hand, Seemingly as Much of Flesh and Blood as My Own, plate 4 of 6,” lithograph in black on ivory China paper laid down on white wove paper, 1896, The Stickney Collection, The Art Institute of Chicago.