Listen to our 2-part conversation with Lisa D. Gray on The Nasiona Podcast‘s episode 28 “Interrogating the Publishing Industry’s White Gaze,” and episode 29 “Protesting the Publishing Industry’s White Gaze,” which are both part of our Deconstructing Dominant Cultures Series.

You can also find our podcast episodes on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Google Play Music, iHeartRadio, and Stitcher.

Episode 28: Interrogating the Publishing Industry’s White Gaze

Episode 29: Protesting the Publishing Industry’s White Gaze

As we try to impact equity in publishing and writing, one critical thing we can all do is buy and read books written by Black and other people of color.

Publishers use Bookscan as one of the metrics that determine who they sign and publish. Authors who see dips in their Bookscan numbers find it difficult to secure deals and contracts. Black and brown writers with wonderful books and track records too often find themselves faced with crumbling careers because the perception is that Black and brown people do not read or buy books.

Representation matters. Seeing and reading books by and about people who share your culture, history, and home creates an unmatched sense of belonging and self-esteem. I remember wandering the shelves of books stores and my local library on a quest for stories about girls and people who looked like me. They existed but not many. As an adult, when I grew into an understanding of what it takes to land a publishing deal and learned about the business of writing, I did what I do in my non-writing life, search for and review data. This search led me to the Diversity Baseline Survey and the VIDA Count.

Numbers matter too. In publishing, as in other industries, editors use numbers to make decisions, and as in other industries, we can use numbers as an accountability tool that allows us to ensure that those in power do not misuse it. The Diversity Baseline Survey and the VIDA Count serve as accountability tools for those of us seeking to ensure that more writers of color and women get published across genres. They act as mirrors for the industry so that it cannot obfuscate the numbers and gaslight us into believing that it, in fact, values our voices.

“The politics of the world of arts and letters have always mirrored the inequalities, injustices and precariousness of the world at large. In the 19th century it was the reason Harriet Jacobs struggled to secure publication for her 1861 autobiography, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl: Written by Herself; why a century later, Zora Neale Hurston disappeared from literary circles without a trace, and why Alice Walker felt driven to go in search of her grave; why coalitions such as Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press emerged in the 1980’s; why today, so many deserving women’s texts—across the globe—remain unpublished or out-of-print, waiting to be retrieved, and why we must not let the word-sisters among us die in obscurity before we call their names and give them the full readership and attention they deserve. It is this urgency which drives VIDA to keep record of our numbers and hold the publishing world accountable.” – The VIDA Count 2019

The most recent (2019) Diversity Baseline Survey and VIDA Count data shows that:

- Across the industry, more white men hold decision making power over who gets published than any other race or gender.

- That men lead the pack in who lands in the pages of literary magazines and journals.

In fact, the Diversity Baseline Survey shows that the industry remains as white today as it did four years ago.

Why does this matter?

As Lee and Low, the organization behind the Diversity Baseline Survey, says on its website, it matters because,

“The book industry has the power to shape culture in big and small ways. The people behind the books serve as gatekeepers, who can make a huge difference in determining which stories are amplified and which are shut out.”

This is true, and so we must find ways to use these numbers as metrics that highlight the gaping lack of diversity and exclusion in an industry that should be accessible for and to everyone who writes and aspires to publication.

It matters because when Black and brown readers fail to find themselves in the stories they read, they question their value and worth. When readers from centered or “majority” groups do not see books by people from cultures and places not their own, it allows them to devalue further the voices and experiences of Black, brown and non-centered or minority groups. They begin to believe that their voices and experiences do not possess a place in the landscape of what and who this country and world are.

Research shows us that people will, when given a choice, choose to work with those who look like them and with whom they perceive themselves to have some cultural connection.

“If the people who work in publishing are not a diverse group, how can diverse voices truly be represented in its books?” – Lee and Low, Diversity Baseline Survey

This must change.

To catalyze change in publishing, we can do a few things.

- Self-publish or start our own publishing houses as many have and are doing in some cases quite successfully. This strategy, however, lets the industry off the hook. It allows it to continue to operate using structurally racist determinants to “open the gate” and to only open it so wide as to let those they deem acceptable or worthy into the fold. It creates the idea of the single story that Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie warns us against in her TEDTalk, “The Danger of a Single Story.”

- Demand equality and equity and seek literary liberation within the current structure. We must find ways to dismantle and dispel myths about who we are as readers and writers. Use the numbers to hold the industry accountable.

- Encourage Black, brown, and white readers alike to buy and read books by Black and other writers of color.

This third strategy impacts the first two. Cross-cultural dialog and engagement are critical to expanding our world views. One of the best ways to learn about other people and cultures is to read books by and about them. As students, Black and brown people read pages and pages of books about cultures and places not our own. This reading gives us a context for how white people think and act. Many school districts’ reading lists, and the revered The Cannon of academia, lack books by and about Black and brown writers. The holes in these lists (and in publishing) mimic the exclusionary nature of the world in which we live and allow non-Black and brown readers to not consider how we experience the world. It centers and privileges whiteness as the norm and marginalizes color and melanated writers.

We need white readers to hear our authentic voices and not those created by (even well-meaning) white writers who filter, and often downplay, our issues. This is not to say that non-Black and brown people can’t write about our experiences but that should not be the entirety or even the majority of those available in the marketplace.

In this age of anti-racist activism, people thirst for reading material that can expand their world views. This thirst frequently translates into the question, “But where do I begin?” This list provides a starting point. It’s for readers searching for themselves on the page and ones who never encountered or meaningfully engaged with someone who doesn’t look like them or share their ethnic/cultural norms and values. These tomes, written by women of color, are ones that you need to read like yesterday. We at Our Voices Our Stories SF love these books and the women who wrote them because they dare to push for space and give voice to the lives of Black and brown women on the page. Buy one today.

The List…

The Fruit of the Drunken Tree, by Ingrid Rojas Contreras

Meeting Faith: The Forest Journals of a Black Buddhist Nun, by Faith Adiele

Playing in the Dark: Whiteness in the Literary Imagination, by Toni Morrison

The Atlas of Reds and Blues, by Devi S. Laskar

A River of Stars: A Novel, by Vanessa Hua

Beloved, by Toni Morrison

An American Marriage, by Tayari Jones

American Street, by Ibi Zoboi

The Street, by Ann Petry

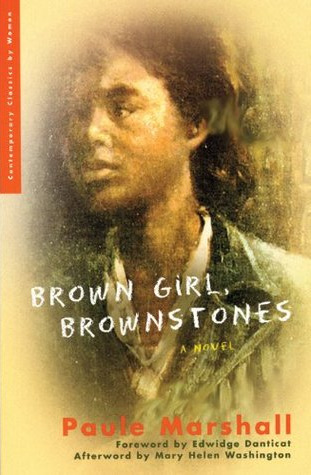

Brown Girl, Brownstones, by Paule Marshall

Mama, by Terry McMillan

You can find links to the books that we’ve featured in Our Voices Our Stories SF on our website and a more extensive one on our Goodreads page.

Attend the Our Voices Our Stories SF virtual book chat event, “The Importance of Our Words: A Literary Experience Exploring The Necessity of Black Voices and Stories with Lisa D. Gray,” on Wednesday, August 26, from 6 pm to 7:30 pm PDT.

(Note: the descriptions and images below come predominantly from Indiebound.org, a Community of Independent Bookstores. Click on the images to take you to the book.)

THE LIST

The Fruit of the Drunken Tree, by Ingrid Rojas Contreras

Seven-year-old Chula lives a carefree life in her gated community in Bogotá, but the threat of kidnappings, car bombs, and assassinations hover just outside her walls, where the godlike drug lord Pablo Escobar reigns, capturing the attention of the nation. When her mother hires Petrona, a live-in-maid from the city’s guerrilla-occupied slum, Chula makes it her mission to understand Petrona’s mysterious ways. Petrona is a young woman crumbling under the burden of providing for her family as the rip tide of first love pulls her in the opposite direction. As both girls’ families scramble to maintain stability amidst the rapidly escalating conflict, Petrona and Chula find themselves entangled in a web of secrecy. Inspired by the author’s own life, Fruit of the Drunken Tree is a powerful testament to the impossible choices women are often forced to make in the face of violence and the unexpected connections that can blossom out of desperation.

Meeting Faith: The Forest Journals of a Black Buddhist Nun, by Faith Adiele

A wry account of the road from Harvard scholarship student to ordination as northern Thailand's first black Buddhist nun. Reluctantly leaving behind Pop Tarts and pop culture to battle flying rats, hissing cobras, forest fires, and decomposing corpses, Faith Adiele shows readers in this personal narrative, with accompanying journal entries, that the path to faith is full of conflicts for even the most devout. Residing in a forest temple, she endured nineteen-hour daily meditations, living on a single daily meal, and days without speaking. Internally Adiele battled against loneliness, fear, hunger, sexual desire, resistance to the Buddhist worldview, and her own rebellious Western ego. Adiele demystifies Eastern philosophy and demonstrates the value of developing any practice―Buddhist or not. This "unlikely, bedraggled nun" moves grudgingly into faith, learning to meditate for seventy-two hours at a stretch. Her witty, defiant twist on the standard coming-of-age tale suggests that we each hold the key to overcoming anger, fear, and addiction; accepting family; redefining success; and re-creating community and quality of life in today's world.

Playing in the Dark: Whiteness in the Literary Imagination, by Toni Morrison

Pulitzer Prize–winning novelist Toni Morrison brings the genius of a master writer to this personal inquiry into the significance of African-Americans in the American literary imagination. Her goal, she states at the outset, is to “put forth an argument for extending the study of American literature…draw a map, so to speak, of a critical geography and use that map to open as much space for discovery, intellectual adventure, and close exploration as did the original charting of the New World―without the mandate for conquest.” Author of Beloved, The Bluest Eye, Song of Solomon, and other vivid portrayals of black American experience, Morrison ponders the effect that living in a historically racialized society has had on American writing in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. She argues that race has become a metaphor, a way of referring to forces, events, and forms of social decay, economic division, and human panic. Her compelling point is that the central characteristics of American literature individualism, masculinity, the insistence upon innocence coupled to an obsession with figurations of death and hell―are responses to a dark and abiding Africanist presence. Through her investigation of black characters, narrative strategies, and idiom in the fiction of white American writers, Morrison provides a daring perspective that is sure to alter conventional notions about American literature. She considers Willa Cather and the impact of race on concept and plot; turns to Poe, Hawthorne, and Melville to examine the black force that figures so significantly in the literature of early America; and discusses the implications of the Africanist presence at the heart of Huckleberry Finn. A final chapter on Ernest Hemingway is a brilliant exposition of the racial subtext that glimmers beneath the surface plots of his fiction. Written with the artistic vision that has earned her a preeminent place in modern letters, Playing in the Dark will be avidly read by Morrison admirers as well as by students, critics, and scholars of American literature.

The Atlas of Reds and Blues, by Devi S. Laskar

The Atlas of Reds and Blues opens with a woman lying bleeding on her driveway, shot by police. The woman has moved her family to the wealthy suburbs, but once there was is met with the same questions: Where are you from? No, where are you really from? The American-born daughter of Bengali immigrant parents, her truthful answer, here, is never enough. The morning that opens The Atlas of Red and Blues is the morning that the woman's simmering anger breaks through. During a baseless and prejudice-driven police raid on her house, she finally refuses to be calm, complacent, polite. As she lies bleeding on her driveway, her life flashing before her eyes, she struggles to make sense of her past and decipher her present―how did she end up here?

A River of Stars: A Novel, by Vanessa Hua

Holed up with other mothers-to-be in a secret maternity home in Los Angeles, Scarlett Chen is far from her native China, where she worked in a factory and fell in love with the married owner, Boss Yeung. Now she’s carrying his baby. To ensure that his child—his first son—has every advantage, Boss Yeung has shipped Scarlett off to give birth on American soil. As Scarlett awaits the baby’s arrival, she spars with her imperious housemates. The only one who fits in even less is Daisy, a spirited, pregnant teenager who is being kept apart from her American boyfriend. Then a new sonogram of Scarlett’s baby reveals the unexpected. Panicked, she goes on the run by hijacking a van—only to discover that she has a stowaway: Daisy, who intends to track down the father of her child. The two flee to San Francisco’s bustling Chinatown, where Scarlett will join countless immigrants desperately trying to seize their piece of the American dream. What Scarlett doesn’t know is that her baby’s father is not far behind her. A River of Stars is a vivid examination of home and belonging and a moving portrayal of a woman determined to build her own future.

Beloved, by Toni Morrison

Upon the original publication of Beloved, John Leonard wrote in the Los Angeles Times: “I can’t imagine American literature without it.” Nearly two decades later, The New York Times chose Beloved as the best American novel of the previous fifty years. Toni Morrison’s magnificent Pulitzer Prize–winning work—first published in 1987—brought the wrenching experience of slavery into the literature of our time, enlarging our comprehension of America’s original sin. Set in post–Civil War Ohio, it is the story of Sethe, an escaped slave who has lost a husband and buried a child; who has withstood savagery and not gone mad. Sethe, who now lives in a small house on the edge of town with her daughter, Denver, her mother-in-law, Baby Suggs, and a disturbing, mesmerizing apparition who calls herself Beloved. Sethe works at “beating back the past,” but it makes itself heard and felt incessantly: in her memory; in Denver’s fear of the world outside the house; in the sadness that consumes Baby Suggs; in the arrival of Paul D, a fellow former slave; and, most powerfully, in Beloved, whose childhood belongs to the hideous logic of slavery and who has now come from the “place over there” to claim retribution for what she lost and for what was taken from her. Sethe’s struggle to keep Beloved from gaining possession of the present—and to throw off the long-dark legacy of the past—is at the center of this spellbinding novel. But it also moves beyond its particulars, combining imagination and the vision of legend with the unassailable truths of history.

An American Marriage, by Tayari Jones

Newlyweds Celestial and Roy are the embodiment of both the American Dream and the New South. He is a young executive, and she is an artist on the brink of an exciting career. But as they settle into the routine of their life together, they are ripped apart by circumstances neither could have imagined. Roy is arrested and sentenced to twelve years for a crime Celestial knows he didn’t commit. Though fiercely independent, Celestial finds herself bereft and unmoored, taking comfort in Andre, her childhood friend, and best man at their wedding. As Roy’s time in prison passes, she is unable to hold on to the love that has been her center. After five years, Roy’s conviction is suddenly overturned, and he returns to Atlanta ready to resume their life together. This stirring love story is a profoundly insightful look into the hearts and minds of three people who are at once bound and separated by forces beyond their control. An American Marriage is a masterpiece of storytelling, an intimate look deep into the souls of people who must reckon with the past while moving forward—with hope and pain—into the future. Combining compelling firsthand reporting from around the world, incisive socioeconomic analysis, and a broad understanding of what's at stake politically and culturally, Immigrants is a passionate but lucid book. In our open world, more people will inevitably move across borders, Legrain says--and we should generally welcome them. They do the jobs we can't or won't do--and their diversity enriches us all. Left and Right, free marketeers and campaigners for global justice, enlightened patriots--all should rally behind the cause of freer migration, because They need Us and We need Them.

American Street, by Ibi Zoboi

In this stunning debut novel, Pushcart-nominated author Ibi Zoboi draws on her own experience as a young Haitian immigrant, infusing this lyrical exploration of America with magical realism and vodou culture. On the corner of American Street and Joy Road, Fabiola Toussaint thought she would finally find une belle vie—a good life. But after they leave Port-au-Prince, Haiti, Fabiola’s mother is detained by U.S. immigration, leaving Fabiola to navigate her loud American cousins, Chantal, Donna, and Princess; the grittiness of Detroit’s west side; a new school; and a surprising romance, all on her own. Just as she finds her footing in this strange new world, a dangerous proposition presents itself, and Fabiola soon realizes that freedom comes at a cost. Trapped at the crossroads of an impossible choice, will she pay the price for the American dream?

The Street, by Ann Petry

“How can a novel’s social criticism be so unflinching and clear, yet its plot moves like a house on fire? I am tempted to describe Petry as a magician for the many ways that The Street amazes, but this description cheapens her talent . . . Petry is a gifted artist,” Tayari Jones, from the Introduction. The Street follows the spirited Lutie Johnson, a newly single mother whose efforts to claim a share of the American Dream for herself and her young son meet frustration at every turn in 1940s Harlem. Opening a fresh perspective on the realities and challenges of black, female, working-class life, The Street became the first novel by an African American woman to sell more than a million copies.

Brown Girl, Brownstones, by Paule Marshall

Set in Brooklyn during the Great Depression and World War II, Brown Girl, Brownstones chronicles the efforts of Barbadian immigrants to surmount poverty and racism and to make their new country home. Selina Boyce is torn between the opposing aspirations of her parents: her hardworking, ambitious mother longs to buy a brownstone row house while her easygoing father prefers to dream of effortless success and his native island’s lushness. Featuring a new foreword by Edwidge Danticat, this coming-of-age tale grapples with identity, sexuality, and changing values in a new country, as a young woman must reconcile tradition with potential and change.

Mama, by Terry McMillan

With her phenomenal New York Times bestseller Waiting to Exhale, Terry McMillan became one of the most important American novelists writing today. Here, for the first time in mass market paperback, is her extraordinary first novel. It is the exhilarating tale of feisty Mildred Peacock, whose five children are her hope and her future.

Lisa D. Gray opens doors and helps other writers of color claim space in writing and publishing by curating several reading series in the Bay Area. She established Our Voices Our Stories SF (OVOSSF) in 2014 as a way to amplify and elevate the voices of women writers of color. The OVOSSF platform allowed her to showcase more than 20 emerging writers and interview authors Natalie Baszile, Renee Swindle, Elmaz Abinader, Jacqueline Luckett, and Tayari Jones. Lisa won the 2018 Edgar Award named for Robert L. Fish and the Henry Joseph Jackson Prize for Distinguished Fiction in 2014. She was a Fellow at the San Francisco Writers Grotto where she is now a member, and has earned writing scholarships to attend The Fine Arts Works Center, The Voices of Our Nations Foundation, and the Vermont Studio Center where she completed a residency. She is currently a fellow at The Ruby San Francisco and holds degrees in English and Creative Writing from Spelman College and Mills College. Lisa believes it is necessary for Black women and women of color to write and share our stories so that others do not erase or control our narratives. She is completing her first novel, Stolen Summer, and is in search of an agent and publisher for her collection of short stories that focuses on Black children coming of age from the 1950s to present day.

Twitter: @ovossf and @randomlisasf

Instagram: @ovossf and @randomlisasf

2 Trackbacks / Pingbacks

Comments are closed.